Disintermediation: The Internet’s Impossible Promise, And Ten Ways It Is Changing Government for the Better

In 2012, social media found itself besieged by discontents, from the literary to the economic, from the fields of technology and of business. The Guardian published a 12,000-word excerpt from Jonathan Franzen's book about a 19th century German cultural critic that panned Twitter, Facebook, and by extension, the entire modern internet. Technology gadfly Jaron Lanier wrote that the internet is destroying middle-class America, and possibly even the foundations of democracy. In Entrepreneurship Weekly, which one would think views the internet rather favorably, author C. Z. Nnaemeka argued (a) that the problems that we are currently solving through digital tools are not really problems and (b) the real problems we face are not being solved through digital tools.

Why such invective for one of the most transformational developments in modern history? The answer lies the very promise of the internet: disintermediation. In one sense, disintermediation can be understood as simply “cutting out the middle man” between, say, a customer and a better deal on a mattress. But the disintermediation of the internet promises even more than that; it’s “cutting out the middle man” between individuals (what Facebook attempts to do) between individuals and information (what online data sets attempt to do), between individuals and their representatives and public servants (what open government attempts to do) and in some cases, between individuals and the physical world (through the internet of things).

The contrarian sensibility captured by Franzen, Lanier, Nnameka, and the cheerfully-perturbed Evgeny Morozov (through articles like "Down With Lifehacking!" and his book To Save Everything, Click Here) resonates because in many ways, the internet, and the social media that it enables, cannot possibly live up to our highest aspirations for it. Twitter might seem at first to connect people to one another, but its 140-character limit soon shows how circumscribed that connection can be. The fact that some people ignore their feeds for days or weeks, and other feeds are written by subordinates, leads some people to discount the medium entirely.

Contrarians aside, the truth is that the internet is reshaping our society in significant ways. Perhaps most importantly, it is changing the relationship between citizens and their government. The better everyone understands the mechanisms of that change, the more we can harness the power, mitigate the risks, and account for the limitations of this new disintermediating platform.

Every Disintermediary Becomes an Intermediary

Though we, as humans, are locked into our own consciousness as completely as drivers locked into their own cars on an interstate, we have always had tools to perceive and try to commune with events and objects beyond ourselves. We invented languages, art, religions, governments, and every form of communication technology from papyrus to MTV so we could more completely make ourselves understood and in turn understand others. So we could, in short, disintermediate our own experience of this world and of each other.

Along the way, each of these inventions--language, art, religion, government, communications technology--has shown itself incapable of complete disintermediation, and met its critics. Art critics ask if painting or the theater even matters anymore, and an entire school of thought argues that even language does not allow us to connect with others entirely.

As the internet becomes as central to people’s lives as art, religion, and even language, we are hearing echoes of the arguments critics have raised to every other medium: Facebook does not bring us closer to one another, it merely occludes our real relationship with our friends (paging Jean Baudrillard!). Twitter does not help us access authentic real-time information, it simply lets us share either the verifiable minutia of our lives (This is my dinner!), the proclamations of pundits that exist beyond truth (such-and-so bill will destroy America!), or statements of fact either unverifiable or verifiably incorrect (more than a hundred thousand people in this march!). Instagram is debasing photography. Spotify is destroying the music industry. Amazon is destroying publishing (and reading). The poet Jerome Stern captured their arguments in the delightful “Bad for You”

But as quickly as we are discovering the capabilities of the internet, we are also witnessing its limitations.

The internet--especially with its social media channels--is one of the most powerful ways for people to access data, physical objects, digital tools, institutions, and each other. That ability to disintermediate has always bumped up against the reality that we can never truly leave the confines of our own minds, and at some point every attempt to do so has failed. Religions withstand iconoclasts, governments withstand anarchists, languages withstand deconstruction, and now the internet must withstand its detractors.

Though they are correct to point out that the internet is not a panacea for every social ill, nor an apothecary for every one of its users' emotional, intellectual, or physical maladies, it is becoming integral to the operation of our complex society. As much as a street brings together two buildings while at the same time demonstrating that there is distance between them, the internet is both giving us access to new tools, to more information, to a wider range of people while at the same time acting as a filter between us and those same things.

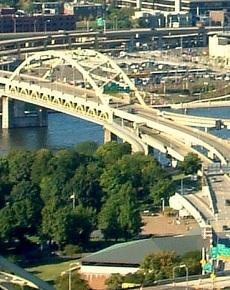

The bridges that connect a city, also divide it: they are both intermediaries and disintermediaries.

Click for full size.

10 Ways to Spur Greater Participation in Governance

Learning the limits and capabilities of the internet is especially important for government employees at every level, from agency leadership to front-line staff. Understanding the capabilities offered by the disintermediating tools available can help encourage more people to participate in government—thus enhancing the legitimacy of government actions, helping provide more transparency, driving down costs, and producing the halo of the Ikea effect. But over-promising can lead to its own problems, so taking into account the limits of disintermediation is essential.

Over the next few months, this series will examine ten different ways the internet is helping us connect more fully with our government and with one another for the purposes of governance.

- Social Media Platforms

- Open Data

- Crowdsourcing

- Distributed Computing

- Crowd Funding

- Ideation platforms

- Co-production and co-delivery tools

- Gamification

- Open Government processes

- Government Apps

It is my hope that, along with my collaborator, Dr. John Bordeaux, we can learn from the efforts in open government since 2009 so that we can design still more effective initiatives using this new, and already indispensible medium.