Six Observations: COVID and America’s Laboratories of Democracy (Part Two)

My last blog examined three observations related to how COVID is effecting the globe, our individual states, and certain populations of our country. This post will cover an additional three observations, all around vaccinations.

Observation 4: Stopping the virus depends on vaccinating the public

Social distancing, masking, and hand washing are important steps to slow the virus, but stopping it depends on vaccinating large numbers of the population. Dr. Anthony Fauci estimates that “herd immunity”—enough for Americans to begin to get back to our daily lives—will occur when between 70 and 85 percent of the population has been vaccinated. To get there, though, requires radically changing the prior vaccination strategy, and to work especially hard in reaching some members of American society.

Lessons:

- The data on the virus’s spread provides important clues about how to prioritize who we vaccinate first to stop COVID.

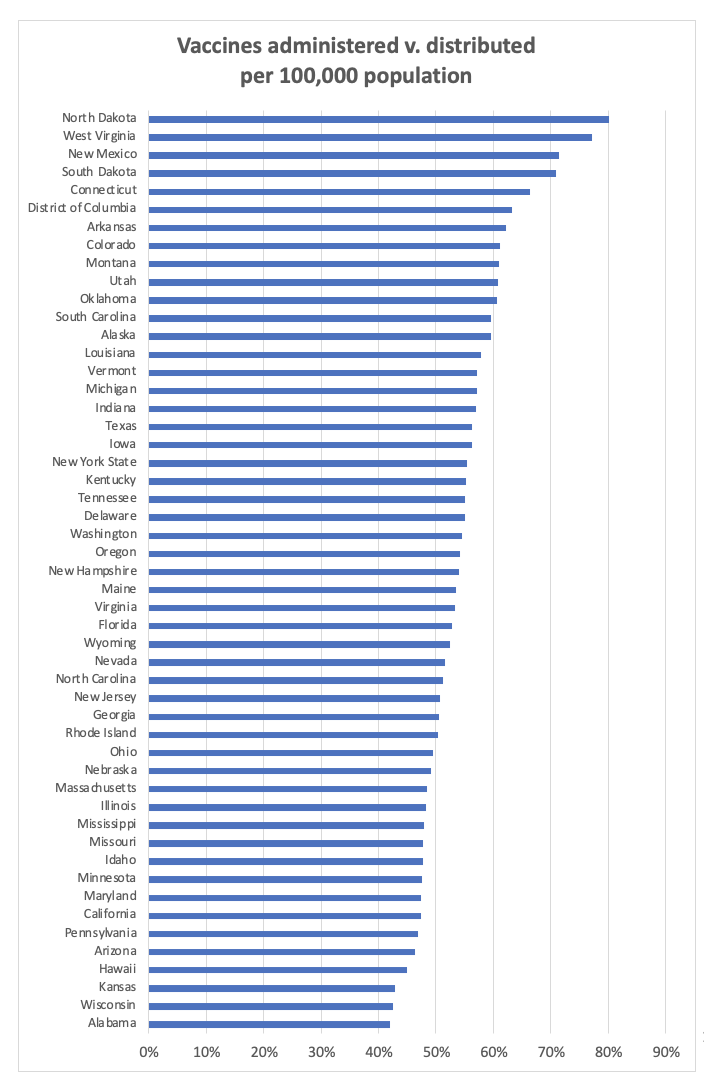

Observation 5: There has been a huge disparity in the effectiveness of the vaccination program so far

There was a real problem in the first steps to getting enough vaccine—and in getting the vaccine we do have into people’s arms. As of January 28, the Centers for Disease Control reports, 47.2 million vaccines have been distributed but just 24.7 million doses have been administered. Some of that comes from the growing pains of launching the most complicated public health initiative in the nation’s history in a remarkably short period of time.

But even given those challenges, some states have done far better than others. The Dakotas, West Virginia, and New Mexico have gotten more than 70 percent of their supply into the arms of residents. At the other extreme, Alabama, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Hawaii have struggled even to reach 45 percent. To stop the virus requires quickly climbing this learning curve, to do more of what’s working and less of what’s not, because the virus pays no attention to state borders. The contrast between adjoining states doing better and those that are not is especially striking: West Virginia, versus Ohio and Pennsylvania; Connecticut, versus New York and Massachusetts; Arkansas and Louisiana, versus Alabama and Tennessee.

The explanation goes far beyond differences among different populations. There have been different political and administrative strategies in different states, and they have produced different patterns in vaccinations. As the Biden Administration takes on a much greater national strategy role, it is critical to figure out what the highest-performing states are doing, and how to replicate their efforts.

Source: Centers for Disease Control, “COVID Data Tracker,” https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations

Lessons:

- As the vaccination campaign got off the ground, there was a wide disparity among the states in their ability to get the vaccines they had into people’s arms. North Dakota and West Virginia were almost twice as effective as Wisconsin and Alabama.

- There is no connection in the data between these vaccination patterns and the previous death rate. It will take time to sort out the patterns that the more-successful states have adopted, but this is a lesson to learn quickly.

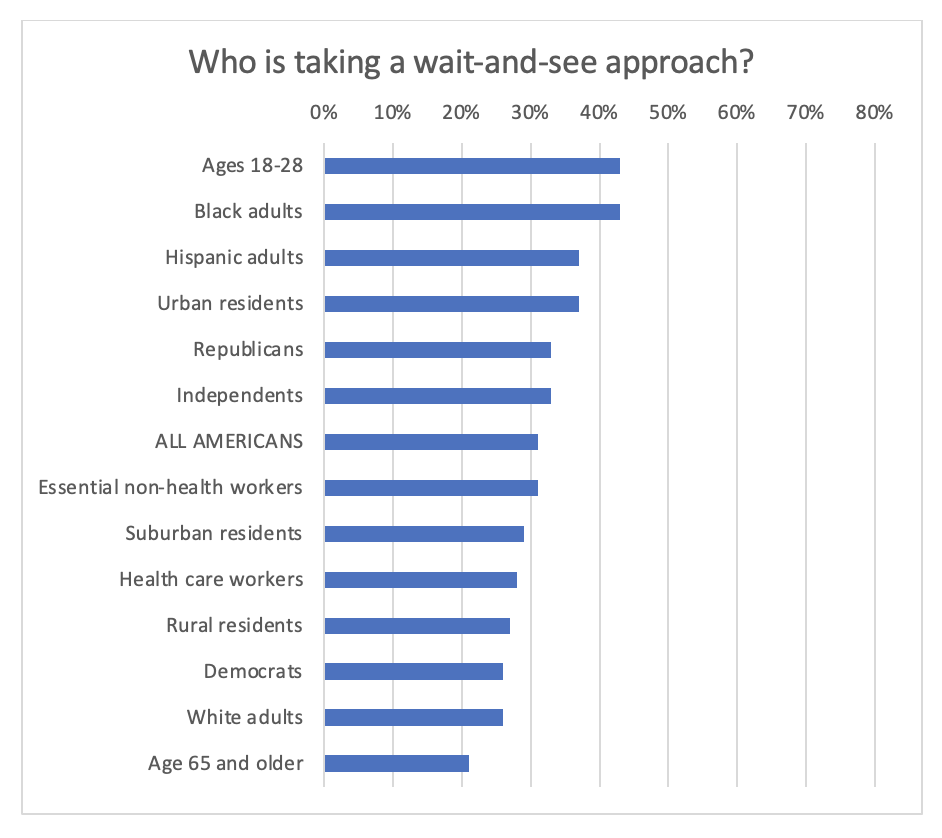

Observation 6: We need to solve the looming crisis of vaccine disparity

Lurking behind the state-by-state numbers is a potential crisis. If the goal is to vaccinate at least 85 percent of the population—and if the nation won’t be able to return to anything like normal living until then—getting the vaccine into citizens’ arms becomes critical. But just as important is ensuring that no citizens are not left behind.

The experience so far, coupled with polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation on which groups are most reluctant to get the vaccine, outlines this dilemma.

Workers in nursing homes, where the outbreaks have been most virulent, have been surprisingly resistant to the vaccination campaigns, with 80 percent of Washington, D.C.-area workers not taking the vaccine on the first round. Digging more deeply, young Americans are far more reluctant to get the vaccine than seniors; Republicans more reluctant than Democrats; and urban residents more reluctant than rural dwellers. And there is great reluctance among Blacks and Hispanics to get the vaccine, compared with Whites.

The roots of these disparities run deep. Some come from the charged rhetoric around the virus and the vaccine, which has created a partisan divide. Some come from the acute vulnerability that older Americans feel, compared with younger generations. And some come from the wide disparities in the availability of health care for some Americans—and their trust in the system.

Unaddressed, this indeed would become a crisis. If the goal is to vaccinate as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, to reduce the spread of the disease, challenges arise on two counts. One count is the reluctance of large parts of the American population, who are sitting back and waiting until they see whether they trust the vaccine. For now, there are long lines waiting for the available shots but, as more vaccine comes from manufacturers, we could face a far longer recovery if many Americans decide to stay on the sidelines.

The other count is the possibility that the early patterns of the virus will replicate themselves in a dangerous spread of inequity. The disease has already disproportionately affected communities of color. If the vaccination process becomes a two-tier system, with Blacks and Hispanics deciding to sit longer before they trust it, COVID will continue to exact a much higher toll in those communities, and they will take an even longer time to recover, multiplying the health consequences upon the economic ones.

The nation is in the early stages of discovering the roots of reluctance—and what to do about it. Blacks and Hispanics, for example, are three times as likely to trust the advice of religious leaders in deciding whether to get the vaccine, providing hints about how to construct a campaign to build trust in communities across the country. This hidden crisis must be addressed to beat the virus down.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor/#hesitancy

Lessons:

- Not only has the virus hit some communities harder than others. The vaccination effort to date has also left many of these same communities trailing. To combat the virus’s potentially uneven impact, it will take a national effort to root out these inequalities.

- This won’t be a matter of just focusing the vaccination effort on the communities that have suffered most to date. It will also require creating different messages for different communities, because the language of trust and the roots of reluctance vary so widely.

Conclusion

The United States has suffered from its strategy over the last year, in which the federal government has passed most decisions onto the states—and where, in some states, the government has passed the important responsibilities onto local governments. It is one thing to license widespread experimentation in the states, but it is quite another to fail to learn the lessons that the experiments teach.

So in summary, here’s what we know:

- In dealing with the virus, the United States has lagged far behind most other countries, including other countries with complex intergovernmental systems.

- The federal policy of devolving responsibility to the states has meant that some states have taken a harder hit from the virus than others—and lack a way to learn what works best in fighting it.

- The virus has hit some American citizens far harder than others: older Americans and persons of color. A strategy that recognizes this inequity—or a plan to address it—is imperative.

- The initial rollout of the vaccine has had widely varying success across the country, with some states doing a far more effective job of getting their allocated supply into the arms of Americans.

- Some Americans, so far, have proven far more reluctant to get a vaccine, especially younger Americans, persons of color, urban residents, and Republicans/Independents. To stop the virus—and especially to deal effectively with the underlying inequities that have already surfaced—requires boosting the vaccination rates of all Americans.

Important patterns are emerging from the U.S. experience so far, including suggestions of which states to watch—and which states are lagging. This series will next dig more deeply into actions that are working to accomplish the critical goal: learning what works fast to beat the virus back quickly, and assessing actions driven forward by the Biden Administration to improve trust, transparency, and performance in addressing the virus that can ultimately help to strengthen supply chains and outcomes across the health care industry.

Image courtesy of dream designs at FreeDigitalPhotos.net